Night of the Hunter

The Rake's Progress: Journalists on Hunter S. Thompson

"Journalism is not a profession or trade," wrote literary maverick Hunter S. Thompson in his seminal 1971 travelogue Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. "It's a cheap catch-all for fuck-offs and misfits—a false doorway to the backside of life." With Thompson dead at 65 from an apparent suicide, the media he so derided is mourning his loss and reflecting on his indelible legacy.

"He inspired a whole generation of writers," said Washington Post writer Helen Benedict, "and brought all kinds of people to non-fiction who might otherwise not have read it." Benedict credits Thompson's off-kilter, highly personal prose—"gonzo journalism," as he dubbed it—with rescuing the field from a "very literary but ponderous state" that appealed only to an in-the-know elite. "He went too far," she said, alluding to Thompson's reputation as a rampant drunkard and pill-popper, "but he's still inspiring. He's the Kurt Vonnegut of journalism."

Thompson's work—even when ostensibly on other subjects, like his recent sports column for ESPN.com—often ventured into the world of politics. "He was one of the most important political commentators we've had in the last 25 years," said Michael Phillips, a lecturer on humor in political rhetoric. Citing Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail, Thompson's groundbreaking coverage of the 1972 presidential election, Phillips said the Louisville, KY-born slugger helped change the course of political reporting. "By saying there was no such thing as objective journalism, he gave the American public a look at the political process that no one had before."

According to Phillips, Thompson's unorthodox methods actually helped, rather than hindered, his access to Washington bigwigs like Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger and Bill Clinton. "Nobody wants to be associated with a suspected scoundrel," Phillips explained, "but if you're a confirmed scoundrel, they'll embrace you."

Phillips also credits Thompson with being one of the first journalists to turn his gaze on his fellow reporters, which was once considered bad form but is now common practice on 24-hour news networks, talk radio shows and Internet blogs. "He was a pioneer in looking at the process" of reporting, Phillips said, "instead of just the results." In fact, journalist Timothy Crouse researched The Boys on the Bus, still the bible of campaign reporters everywhere, while working as Thompson's assistant covering the 1972 election.

Somewhat more tenuous, however, is Thompson's place in academia. Should a reporter who rarely stayed on topic, openly abused drugs and alcohol, and never met a deadline he couldn't ignore, be held up as an example for journalism school students to follow?

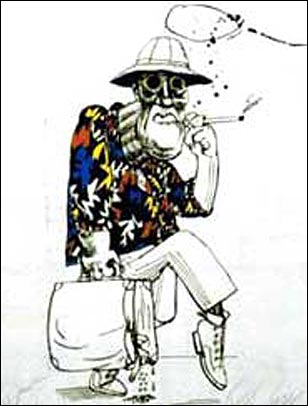

"Young writers should read Thompson just as they read all sorts of talented writers," said Thomas Kunkel, dean of the University of Maryland journalism school and editor of the American Journalism Review. "Thompson was to modern journalism what Salvador Dali was to modern art—alarming, personal, hyperbolic, overly dramatic and unafraid to tackle big themes." But like Dali, Kunkel explained, Thompson learned the rules before breaking them. "It's easy to forget that in the beginning," Kunkel said, before the drinking and drugs threatened to turn Thompson into a beady-eyed lampoon, "there was this alarming talent."

Still, Kunkel warns his students against trying to mimic the godfather of gonzo journalism in their own writing. "Only Hunter S. Thompson could do it—and at time, even he couldn't pull it off."

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home